Artworks that may be simultaneously experienced by the entire planet represent a revolutionary development in the history of the visual arts.

In 1911, Wassily Kandinsky wrote:

“The great epoch of the Spiritual which is already beginning, or, in embryonic form, began already yesterday……provides and will provide the soil in which a kind of monumental work of art must come to fruition.”

The British art historian Herbert Read (1967) has written:

“The artist and the community are profoundly interrelated. Traditionally, artists have been channels for the tempo, the tone and the intensity of their society. The function of their art is to express feeling and transmit understanding. In a genuine work of art one recognizes what is being shared by our common humanity. Artists achieve this through an intuitive appreciation of the appropriate form and through the use of materials made available to them by the circumstances of their time.”

“… art is a direct measure of humankind’s spiritual vision. The great monuments of the past were celebrations of a communal vision which was closely bound up with some form of religion. Religions created myths to explain their perceptions of the universe and art served to convey these myths.”

Since the beginning of our civilization and perhaps since the advent of human consciousness, the artist and the scientist have been partners in the task of communicating our understandings of the nature of the universe. It has often been stated that the scientist and the artist are very similar, especially in their approach to exploring and investigating their particular subject matter. In earlier times the scientist and the artist were often one and the same person – Leonardo Da Vinci being the most obvious example.

Today, the complexity of current society has led to increased specialization which in turn, appears to have contributed to a lack of mutual appreciation and understanding between the arts and the sciences. The sheer volume of information available today augments this situation. Furthermore, the fear of the environmental consequences associated with technology used for weapons development, power production, genetic manipulation, chemicals, surveillance and information control (to name but a few areas of concern) have created a widespread mistrust for advance technology among the general public. Artists have in turn, expressed and included these fears in their works, or reacted by avoiding or confronting this situation by pursuing avenues of artistic semantics understandable mostly to their peers and critics.

It was the early works of science fiction and the descriptions and depictions of the cosmos by artists of a hundred years ago that stimulated the first space pioneers. In addition to the vast amount of science fiction literature about space that has for generations stimulated our imagination about exploring the cosmos, a highly diverse genre of visual art has also emerged called: Space Art. As humanity’s breakout into space is considered to be one of the most significant achievements of the 20th century, it is no surprise that that space exploration became firmly integrated into contemporary culture. This is surely evident in the cinema as the many blockbuster films about space have become the most financially successful and popular forms of space art and, as such, they have contributed significantly to keeping the idea of space exploration firmly embedded in the public’s imagination.

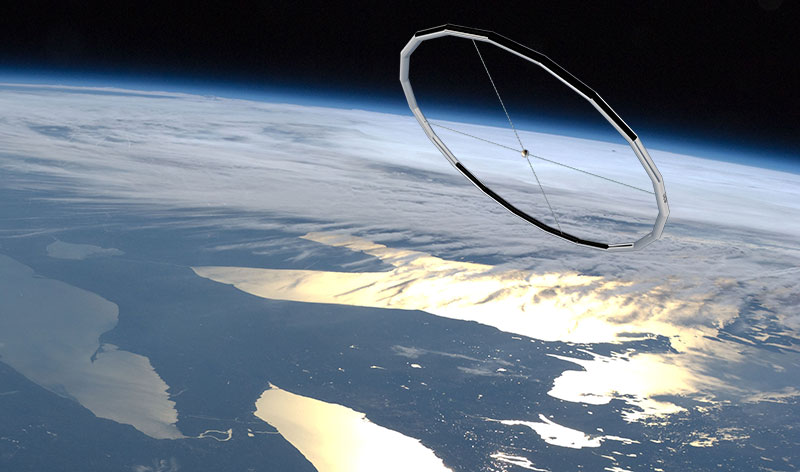

Recent developments in the commercial use of outer space – the NewSpace industries – have made it more easily possible for cultural events and objects to enter Greater Earth. Artworks that may be simultaneously experienced by the entire planet represent a revolutionary development in the history of the visual arts. But access to the world audience via space technology is more than just a unique opportunity for the creation of globally experienced art works. Artworks in the region of Greater.Earth designed to be visible to the world’s population will almost invariably be symbolic and will attempt to communicate universally understood values and understandings. They may also be opportunities to link space activities with the future well-being of our planet as well as opportunities to include the participation of a large international public in their realization. At the very least, they will provoke controversy and discussion.

Furthermore, as art “knows no boundaries”, artworks in the space environment may contribute to more international understanding through the simultaneous and global sharing of these unique cultural events. They may contribute to international cooperation through the necessary involvement of various international cultural and political partners. They will require the collaboration of scientists, engineers and artists once again working together in mutual understanding and respect of each other, and, on another level, the cost and complexity of bringing these works to completion will involve the participation of the industrial and the financial community.

As such, they may have a transforming influence on some of our assumptions and technologies, finding new areas of application and direction. By becoming a new customer for the talents of these industries, their eventual realization may be a driver to future cultural experiments in this environment – a stimulant to future visionary creative thinking.

If the advent of space exploration and development is truly a signal that our species and life itself is about to make an evolutionary jump of cosmic proportions, then an art of comparable significance will be an essential ingredient to its success. The time has come to put our whole culture into Greater.Earth by adding a Cultural Dimension to our extraterrestrial vision and art to its development. This art will invariably be global, monumental, visionary, and will use space itself as a new medium of expression.

This article is an updated excerpt from:

Arthur R. Woods & Marco C. Bernasconi (1989 ), The OUR-Space Peace Sculpture: Introducing a Cultural Dimension Into the Space Environment. – Paper IAA-89-673 presented to the 40th IAF Congress, Torremolinos, Spain. October 7-13.

- The Spiritual in Art – Abstract Painting 1890-1985, LACMA, 1986 (See also quote)

- Read, H. (1967), The Meaning of Art. Farber & Farber. London, 1967 pp. 262-268.